How Technology can Solve the Challenge of Reentry

Olivia Button

As the features within Unite Us develop and mature, leaders in different fields look to our team for guidance on how these tools can be implemented to meet their goals. One mission that continues to surface is the improvement of the reentry experience for people returning home from jail or prison. While we could begin this post by regarding reentry programs as a cost-saving mechanism for local, state, and federal governments and showing how Unite Us fits in to that picture, that would not serve our company’s purpose. Reentry programs in the context of our work are meant to reintegrate people in to society before and after they leave jail or prison in hopes that the transition is compassionate, coordinated, and successful. Though it is important to identify ways to reduce recidivism, and subsequently, government and taxpayer spending, a person’s humanity should always be the center of reentry work. With that, this post is meant to highlight what a person needs upon leaving jail or prison, tools to connect a person with those needs, andhow to implement those tools throughout a community.

The People and Services Inside

To create a compassionate care coordination model in this context, it is important to first acknowledge the whole person, not just the person leaving jail or prison. We need to explore what their lives might have been like prior to arrest or incarceration and inside to fully understand what services and support they might need upon release.

First, jail and prison populations are largely composed of people who were poor before arrest or incarceration. A study by the Prison Policy Institute found that in 2014, incarcerated people had a median annual income of $19,185 prior to their incarceration, which is 41 percent less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages.1 There are approximately 53,000 youth held in facilities due to juvenile or criminal justice involvement, and most are held in detention centers operated by local authorities. With an education stunted, it is not surprising that a quarter of formerly incarcerated people do not have a basic high school diploma or GED.2

Regarding health conditions, it is estimated that half of people in USjails and prisons have a mental illness. In her book Insane: America’s Criminal Treatment of Mental Illness, Alissa Roth found that of all women in state prison, 75 percent have a mental illness, compared to 55 percent for men. Women involved in the criminal justice system are more likely to have experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse, trauma, and have substance use problems. Last, the number of people incarcerated for drug offenses is 11 times that of what is was in 1980. The Center on Addiction asserts that of the 1.5 million people in jail and prison who met clinical diagnostic criteria for a substance use disorder in 2006, only 11.2 percent had received any type of professional treatment since admission.3 Despite evidence of effective treatments, the two most common forms of approaches to people convicted of drug offenses are self-help programs and drug education/awareness programs.

Roth makes an acute observation in her studies of mental healthcare in prisons: corrections officers are the eyes and ears of the clinicians in noticing who is sick and who needs treatment. However, privacy and HIPAA rules prevent them from accessing medical records, and officers are trained to maintain order, not to notice particular behaviors and respond accordingly. Unfortunately, this and other fundamental problems including overcrowding, shortage of providers, and lack of funding for facilities has caused healthcare for people in jails and prisons to majorly suffer.

The goal of jail and prison is at odds with what a person might need; deprivation and incapacitation do not lend to a rehabilitative environment. Because jails and prisons lack the theoretical and financial attention to basic needs and treatment, the stage is set for complication upon release and a cycle between correctional and community agencies.

What a Person Needs

Let’s run with an example: James is incarcerated in a New York State correctional facility. James has a group of friends inside, a job, shelter, and healthcare. James suffered from alcohol addiction prior to being incarcerated and takes an antidepressant medication. He is attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in prison and rarely sees his family or friends, as the correctional facility is about a five hour drive from his home. James is looking forward to his upcoming release date—he was granted parole after serving his minimum sentence.

James lives in a highly structured, non-autonomous environment with little control over obtaining the services he needs. If he is unsatisfied with the pay at his job, the amenities of his shelter, or the people he spends time with, he cannot change his circumstances. However, once James returns home, he will have complete freedom with none of the structure or guarantees that prison provided.

While care coordination plays a role in connecting people to diverse needs, it also lessens the shock of transitioning back to autonomy and life without structure. The Women’s Prison Association outlined basic life areas that shape a person’s success when returning to the community that include livelihood, residence, family, health and sobriety, criminal justice compliance, and social/civic connection.4 We will use a few of these categories to dig deeper into what a person needs upon returning home.

Residence

This is likely the most defining need for a person’s reentry success; without shelter, people leaving jail or prison are at high risk for recidivism. The Prison Policy Institute postulates that formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public.5 Affordable housing is scarce in most places around the US, and public housing authorities can obtain criminal records for all applicants, which makes for great uncertainty when arranging reentry housing.

If James decided to apply for public housing, he would need to present evidence of his rehabilitation and treatment, but he could be permanently or temporarily barred from living in public housing depending on the nature of his crime. Otherwise, James needs to establish a residence at a family member’s home or contact local reentry organizations that offer transitional housing. He might also consider supportive housing, given his past experience with alcohol addiction.

Family and Support

A person’s social support is vital to the success of their transition from jail or prison. If we revisit our example, we can think about James going home to a family and a group of friends he has seen only a handful of times over the period of his sentence, if at all. How can he reconnect to his community after so much time away? What will happen if he doesn’t find a group of people to support his transition?

According to the Prison Policy Institute, less than a third of people in state prisons receive a visit from a loved one in a typical month — disconnection between families or friends make reentry difficult.6 James needs to reconnect with his family or find a group of like-minded individuals to spend time with upon his return. To do so, he might need to start calling friends to reacquaint himself with those relationships, encourage family members to pick him up once he is released from prison, or get in touch with local organizations that host support groups.

Healthcare

People in prison are the one population of Americans guaranteed healthcare by law. However, having to reconcile between disciplinary and therapeutic methodologies renders some treatments ineffective and wasteful. People receiving more intense healthcare services inside, like medication-assisted treatment, Hepatitis C treatment, or treatment for serious mental illness will need to prioritize discharge planning to prevent a delay in care. Even less intense treatments require coordination when a person leaves jail or prison, like diabetic patients and older adults who will need increased access to healthcare as they age in the community.

The challenge faced by people in jail or prison is having to cross a frontier between two separate systems for funding medical care (jail/prison to community), which typically translates into disconnected provision of care. The challenge for us is designing the system that connects people to insurance and care before they are released and organizing this disconnected frontier.

In our example, James needs to find a physician in efforts to continue his antidepressant medication, and identify an Alcoholics Anonymous group, should he wish to remain involved. To address his healthcare needs and prevent gaps in treatment, we might formalize the links from jail or prison to community-based treatment and emphasize the importance of aftercare with correctional staff planning for his reentry. His reentry plan should include the transfer of health information to local providers along with his prescription list.

Next, let’s imagine what the reentry process could look like if there was greater investment in the livelihood of people inside.

Tools to Connect a Person to those Services

There are tools to connect a person to the things they need today: email, phone calls, existing partnerships, meetings, and even reentry case management software. In New York State each person in prison is required to complete a community reentry preparation program within 120 days of release under the supervision of a Transition Service Counselor. According to the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, participants are “provided a ‘portfolio’ to assist in organizing documents (e.g., birth certificates, social security cards, resumes), keeping vocation and education certificates in one place, locating reentry strategies and plans, and preserving service referral information and employment related materials.”

If this sounds like a folder full of paper documents, that is exactly what it is. Though these tools certainly support the coordination of basic needs, what if we could make the reentry process smarter, more secure, and positively impact the aforementioned statistics? We think it’s possible.

Back to our example: James is preparing for his release and his transition service counselor has identified a few basic areas of life that need to be addressed prior to release. James does not have substantial social support where he is being paroled and he needs to connect to healthcare providers and substance use treatment. Before the counselor gives James the contact information for a support group or emails a case manager at a local community-based organization, let’s step back and examine what could be implemented prior to this initial contact.

Screening

The Council of State Governments Justice Center has collected great information on the reentry process; in one report, the author states “[l]ocal jails, state departments of corrections, and community corrections agencies each employ distinct assessment procedures and maintain independent information systems, impeding the transfer of information from one corrections agency to another.” Just like in other care coordination settings, there are siloed systems that make it difficult for information sharing and inter-organization communication. Agencies experience duplication of work, while clients incur stress by having to recount their needs to multiple community partners.

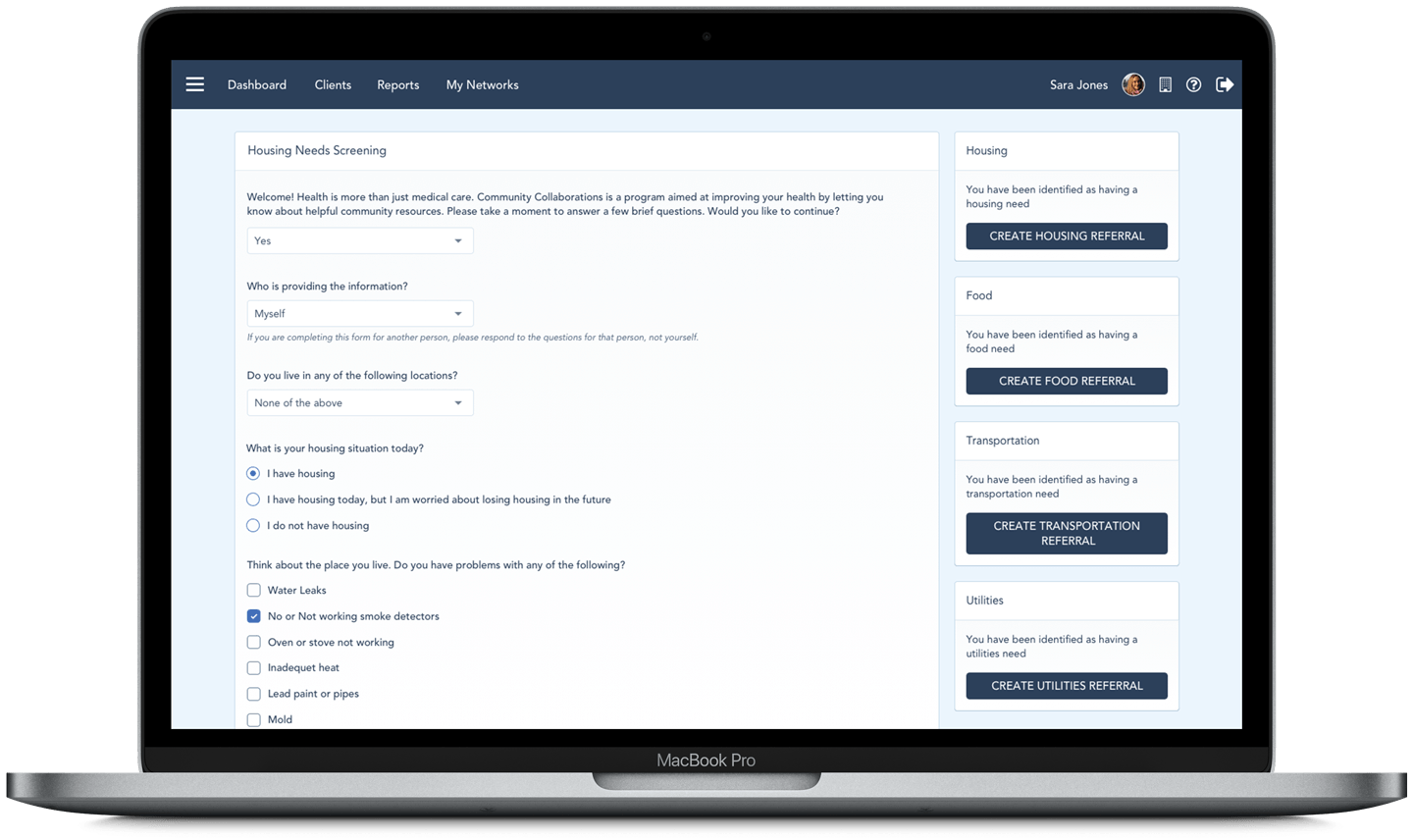

By using one tool that relays pertinent information between organizations through referrals, agencies can share the most amount of baseline information at one time, while maintaining internal assessment procedures. Using Unite Us, staff members complete a screening with a client that generates suggested referrals based on the client’s answers. In coordinated care networks focused on reentry, a screening might include questions pertaining to the person’s basic life areas and generate referrals to organizations offering that service. It can also surface health needs and initiate enrollment in healthcare coverage prior to being released.

What is unique about our screening tool used in a reentry context is that it effectively reconnects a person to the autonomous and digital world they will soon join. Instead of asking someone to keep a folder with paper documents that are easily lost, damaged, and generally unprotected, a screening captures important information, sends it directly and securely to an organization that can help the client, and eases the transition to receiving services on the outside.

Securing Reentry Plans

Anothercrucial element of coordinating reentry services is the finding available services in the community once a person is released. If we want reentry to be as smooth and simple as possible, a person leaving jail or prison needs to be directly connected to a staff member or healthcare provider in the community who is expecting their release and return rather than being left to find services on their own. If reentry plans are not secured prior to release, it is highly likely they will reoffend or recidivate. We also know that without aftercare in place, any progress made from substance use treatment in jail or prison may be lost, and after being released people may return to drug use.

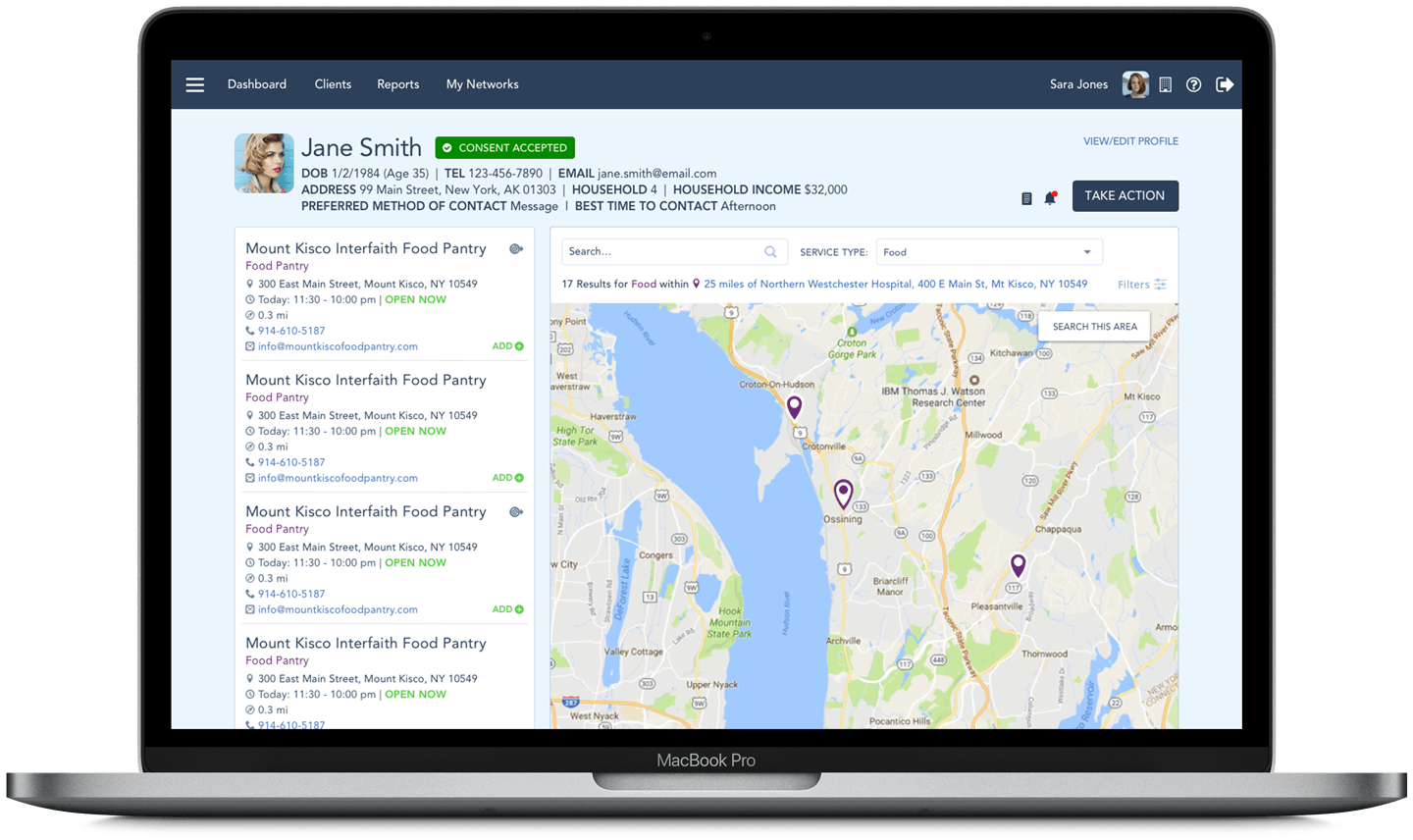

To connect people to the services they need, we must understand the organization’s capacity and program eligibility requirements, and keep these data points up-to-date in real time. As soon as a referral is started in Unite Us, transition service counselors can view organizations on a map in relation to the county to which the person is paroled. This map can be filtered by services offered, program eligibility requirements, and proximity to the person’s home address. If upon receipt of the referral an organization does not have capacity or the client is ineligible (e.g. not enough beds, cannot serve people with certain convictions, etc.), the referral can be rejected and sent back to the original sender for further assessment.

Similar to traditional coordinated care networks, the act of ensuring an organization can serve a client before they arrive is a major stress relief for both the people seeking and delivering services. For networks that are reentry-focused, the referral mechanism in Unite Us provides an additional layer of support to a person whose success in the community critically depends on their access to care.

How to Get Started

Before a reentry program or initiative can begin using these tools, there needs to be a group of stakeholders that is interested in improving the transition from jail or prison to society. So who makes up this group and who values this process?

Like other coordinated care networks getting off the ground, organizations looking for technology solutions to improve the transfer of client information typically know exactly who should be involved. Corrections, nonprofits, public agencies, and health systems that serve people inside jail or prison stand to benefit from joining a network because of the opportunity to transfer health, legal, and other information on a secure platform where they can see the results of their referrals in real time.

This work is beginning to take shape. The Urban Institute has developed strategies for connecting justice-involved populations to healthcare coverage where state Medicaid agencies provide incentives in contracts for managed care organizations (MCOs) to support care coordination activities as enrollees transition from jail or prison back to the community.7 In Ohio, MCOs supported the discharge process for people with high needs and included selection of one of the five managed care plans into the prerelease Medicaid enrollment process. Each enrollee is given a Medicaid ID card upon release and an appointment for follow-up if necessary. The key to constructing an ecosystem that supports people leaving jail or prison is to identify partners that will actively participate in care coordination and uphold the mission and standards of the network.

Once reentry care coordination processes are established, communities can even look to diversion or alternatives-to-incarceration programs to implement similar tools. For example, people in drug court often have the same needs as a person leaving prison or jail and the organizations that offer these services may overlap. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves — if you have questions about using Unite Us to build a coordinated care network, please send us a message:

About Unite Us

Unite Us is the nation’s leading software company bringing sectors together to improve the health and well-being of communities. We drive the collaboration to predict, deliver, and pay for services that impact whole-person health. Through Unite Us’ national network and software, community-based organizations, government agencies, and healthcare organizations are all connected to better collaborate to meet the needs of the individuals in their communities.